Injuries to tendons are common at all stages of life. There are a number of factors that can increase the risk of suffering a tendon injury including age, sex, genetics, concurrent diseases (i.e. diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, smoking, obesity), and inadequate rest and recovery between bouts of exercise/work. Inactivity and lack of loading have a powerful effect on the maintenance of tendon health as well.

Tendon injuries can occur for a wide variety of reasons and have three classifications that are commonly used:

Tendonitis - Characterized by inflammation. (covered below)

Tendonosis - Characterized by degenerative changes to the tendon structure. Repetitive strain that does not heal fully over a longer period of time.

Tendinopathy - An inclusive term that relates to the pain and reduced function of tendons during injury and recovery.

Injury to a tendon can be due to both to a single event or due to a repetitive stress over time. A single event could be an accident at high speeds, or a tissue under a heavy load. The other end of the scale is injury caused by repetitive stress that adds up over time, leading to a situation where the tendon fails to cope. This can lead to an increased risk of tendon injury during relatively normal daily activities.

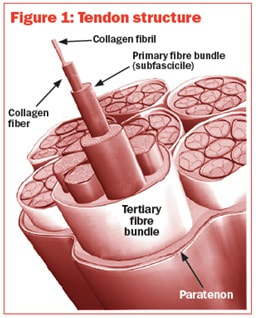

There are two main types of collagen inside the tendon, referred to as Type 1 and Type 3 respectively. Type 1 is thicker and able to handle heavier forces. Type 3 collagen is thinner and helps to develop the framework for the tendon. Several theories exist as to what may actually cause the change in tendons that lead to injury, the most popular involves a lack of oxygen in the tissues and the effect that inflammation has when it occurs repeatedly over a longer period of time. This boils down to an inability for the tendon to maintain the balance between new collagen fibers and the natural loss and change that happens with age and activity. Over time, the structure will change in a way that makes the tendon less able to handle stress and load.

What is quite interesting is that these structural tendon problems are relatively common in the general population. Up to 13% of people in their 50s, 25% of people in their 60s, and 50% of people in their 80s will demonstrate a full thickness rotator cuff tear. More importantly, is that some of these people will have minimal or no symptoms at all. Ultrasound and imaging only tells ua a part of the story. Painful symptoms are poorly matched to Ultrasound findings, meaning that a high percentage of patients that show positive findings on imaging do not have any related pain or symptoms.

Typically, tendon healing will go through three different stages of recovery during the healing process.

Inflammation - Days. Immediately after acute injury, the body will release certain chemicals and molecules that bring immune cells to the injury site. Their first job is to remove any dead or damaged tissue that will not recover and to make room for the next phase of recovery. These chemicals have the unfortunate side effect of making the area tender and sore on average, but is necessary for our body to move forward.

Proliferation - Weeks. Once the body has completed the inflammatory phase, new cells will be laid down in the tendons to repair the damage. Depending on the extent of the injury this process can take up to several weeks. These new tissues will be immature and not yet used to the stresses of daily activity. During this time there may be some more sensitivity in the area as new blood vessels and nerve endings are developed as well.

Remodeling - Months to Years. Once the new tissues have been incorporated into the existing tendon, the remodeling process can begin in earnest. This period of time actually encompasses our whole lives as we are constantly changing our bodies as we grow, age, and engage in meaningful activities. From a healing perspective, this can take months or even years to fully develop the tendons that were a part of the injury. While this can seem daunting in its scale, it is also a huge source of optimism as even older injuries and complaints can often be improved with effort.

Despite the various options that exist to treat tendon injuries, they can sometimes result in reduced function and disability for months. Even with successful treatment, some will be left with a tendon that is weaker than previous and potentially more susceptible to injury in the future. While tendons have the ability to regenerate to a degree, the current thought is that the highly ordered structure that it began with will likely not return to preinjury levels after injury and recovery. After the healing process, tendons contain a higher concentration of the Type 3 collagen, which are typically thinner fibers, resulting in an overall weaker tendon. This can be changed to a degree over time by developing the strength of that tendon, but how much depends on the severity, location, and circumstances of the injury.

So what can be done about this then?

1. Manage and guide the inflammatory process. Everyone will have different needs when it comes to this. Inflammation is a natural and necessary part of recovery. However, if this period is prolonged, it does not allow for transition into the later stages.

2. Maintain movement and mobility. While immobilization has been demonstrated to be useful in post-surgical tendon recovery and for other types of tendon injuries, this must be balanced with keeping the affected area moving and functional.

3. Develop structure and strength of the tendon. Once the tissues enter the remodeling stage it is important to introduce loads and activities that will help that tendon to grow and adapt to each person’s needs and environment. Muscle loading is necessary for the development and maintenance of tendon size and strength, but this needs to be done carefully at times.

I hope that this information will assist in the understanding of this very common condition. As always, if there are any questions or comments regarding this material, please feel free to contact our office directly.

-Trent, PT

References

● Tendinopathy: injury, repair, and current exploration. Lipman, K et al. 2018. Drug Design, Development and Therapy.

● Mechanisms of tendon injury and repair. Thomopoulos, S., Parks, W., Rifkin, D., Derwin, K. 2015. J Orthop Res.

● Review: Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of tendinopathy. Dean, B., Dakin, S., Millar, N., Carr, A. 2017. The Surgeon, Journal of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Ireland.

● Tendon Basic Science: Development, Repair, Regeneration, and Healing. Andarawis-Puri, N., Flatow, E., Soslowsky, L. 2015. J Orthop Res.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed