I encourage anyone interested to look back at the previous blog post on pain for some background information on the factors involved in pain and tissue sensitivity at a local level. Once symptoms and dysfunction persist for a long enough period of time, they begin to enter a period that is referred to as chronic. When things get to this point, a number of other changes and adaptations begin to take place within the body. The portion that we will be focusing on today is the idea of the sensory homunculus.

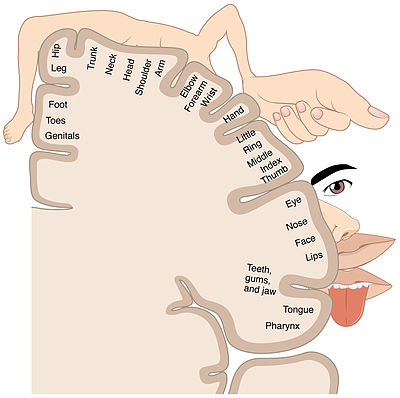

The homunculus refers to a representation, or “map” of our body that resides within our brain. Every time we feel something from a particular body part, or move a particular body part, there is a corresponding activity in the part of the brain that is assigned to that area. This has many benefits, including allowing us to be aware of our entire body at any time, simply by thinking about it. Even with our eyes closed we can make very precise movements, such as touching our nose or ears with millimeter accuracy. Below is an image that shows how the homunculus is laid out in the brain.

As discussed in my previous post on Chronic Pain, the connections between neurons gets stronger and stronger the more that they are used. Connections that are used less often become weaker as well. So, the piano player or avid knitter will have a larger representation of their hands and fingers in their brain compared to someone who has spent more time playing soccer or cycling.

In the context of pain, the connections between the injured tissues and the homunculus are very important. When constant signals are being presented to the brain for interpretation, those nerves get better and better at transmitting signal. The brain also gets better and better at looking out for it and can become overly sensitive or hypervigilant. Over time this can change the size of the body parts on the homunculus. This can lead to problems.

For example, as the homunculus changes and as nerves grow more sensitive things that normally would not bother the tissues can become irritable, and even completely normal things can now become painful. What happens next is very interesting. As the nerves and brain become more sensitive a point can be reached where the adjacent parts of the homunculus start to become involved. Enough chemical and structural changes have occured that the elbow now becomes involved in a shoulder pain, or a hand joins a wrist in calling out for help. The secondary body part was not injured, sick, or in any danger, but it starts to become a part of the presentation.

One of the more disheartening things that can come out of a discussion on Chronic Pain is that people will ask for “a new back”, or request that a body part be “chopped off” to make the pain go away. While it is usually said with a touch of humor in the voice, it indicates some potentially more serious issues with the pain presentation and how people are coping with the situation.

Coming back to the homunculus, the map of our body within the brain itself, these talking points are some of the first signs of dissociation. This is the idea that the brain will try to distance itself from the symptoms, the pain, and eventually the body part, to try and cope with the environment. You can think of this as the brain trying to “smudge” the drawing of the body part to make the symptoms less powerful and less distinct. It can be seen in more extreme cases and nerve injuries with people failing to recognize their own limb, or reaching a point where they lose the conscious ability to move/operate the muscle/joints in that area (Although this is quite rare).

What can be frustrating at times is that this system does not change very quickly after symptoms have persisted into a chronic state. However, I would argue that it is actually a very valuable thing that this map of our body inside the brain and the nerves involved are slow to change. If the system could change at the drop of a hat in a positive direction, it would also be easier to change it in a negative direction. The strength of this system relies on the ability to handle a significant amount of stress from our environment without permanently affecting the tissues in our day to day lives, but will start to transform over time in the presence of repeated challenges. This means that since it took some time for the pain presentation to get to where it is, the recovery process will also take time and many repeated efforts. This can be difficult at times as the attempts to change are often uncomfortable, fatiguing, and usually more effort/work than has been tried previously.

What can be done?

The most positive aspect of all the information discussed above is that the brain and the nervous system are highly plastic and able to change, over the course of the entire lifespan. Knowing what is happening and knowing that there are options is a powerful tool in the fight with chronic pain. The brain, the tissues, and the homunculus can adapt if they are given new stimulus and new ways of doing things. This helps to develop new connections and new pathways of communication. This helps to sharpen the mental image of what that body part does, how it moves, and what it is capable of.

From a physiotherapist standpoint this means that the map of our body inside the brain can be changed with repeated efforts. We can sharpen certain areas, un-smudge others, and generally improve the communication and function of these brain areas by giving them repeated movements and encouraging a less stressful interaction with all of its neighbours. This will typically consist of a combination of education, breathing/relaxation techniques, and appropriately challenging exercise. It is often difficult to make general statements about what will work, since every individual will have a different experience.

I understand that this may create more questions than answers for a number of people. Because of how individual all of these experiences will be, I have not found a satisfactory way to outline everything in general terms. If there are questions about what you have read today, please feel free to leave a comment or reach out to our office directly. There will also be a free seminar on February 20, 2019, at our office, where I will be covering these topics and more related to Chronic Pain and management/treatment options.

● Trent, PT

References

● Modern pain neuroscience in clinical practice: applied to post-cancer, paediatric and sports-related pain. Malfliet, A. et al. 2017. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy.

● Neuroplasticity of Supraspinal Structures Associated with Pathological Pain. Boadas-Vaello, P., et al. The Anatomical Record 2017.

● Pain and Plasticity: Is Chronic Pain Always Associated with Somatosensory Cortex Activity and Reorganization? Gustin SM, Peck CC, Cheney LB, Macey PM, Murray GM, Henderson LA. The Journal of Neuroscience 2012.

● Chronic pain-related remodelling of cerebral cortex - ‘pain memory’: a possible target for treatment of chronic pain. Lithwick, A., Lev S, Binshtock A. Pain Management 2013.

● Functional imaging of allodynia in complex regional pain syndrome. Maihofner C, Handwerker HO, Birklein F. Neurology 2006.

● https://www.physio-pedia.com/Chronic_pain_and_the_brain. Retrieved Jan 15, 2019.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed